Cover photo by Dr. Gerry Farrell

This book explores the power that a single industry can wield over an entire province, namely Nova Scotia in eastern Canada. It is a story that has been waiting to be told. With a powerful foreword by Elizabeth May, leader of Canada’s Green Party and Member of Parliament for Saanich-Gulf Islands, British Columbia, it has local, national and even global relevance.

November 2017

Fifty years ago this month a long list of dignitaries and politicians gathered at Abercrombie Point in Pictou County, northern Nova Scotia, for the official luncheon and opening of the brand new pulp mill owned by Scott Paper of Philadelphia.

Since it went into operation in 1967, the mill has provided valuable jobs and found support from governments of all levels and all stripes. But it has also fomented protest and created deep divisions and tensions in northern Nova Scotia.

Twelve premiers and five foreign corporate owners later, the mill remains a smelly fixture across the harbour from the picturesque waterfront of Pictou, the birthplace of New Scotland.

Its fascinating story is one that has been waiting to be pieced together and told. And that is what Nova Scotian journalist and award-winning author Joan Baxter does in the new book The Mill: Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest.

Picturesque Pictou waterfront across from the pulp mill. Photo by Joan Baxter

It meticulously and dispassionately documents the history of the Pictou County mill using archival material, government records, consultant and media reports, and poignant interviews with people whose lives have touched by the mill and the pulp industry. By weaving these personal stories into the historical narrative, the book brings to life five decades of controversy and citizen-led campaigns to have the mill clean up its act, and to have government protect the people and environment rather than lavishing hundreds of millions of dollars of financing and other concessions on a mill owned by large corporations.

Boat Harbour in June 2016. Photo by Joan Baxter

This book takes readers to Pictou Landing to hear from members of the First Nation there, and learn about their betrayal by both provincial and federal governments, which turned Boat Harbour – so precious to them that they called it “the other room” (A’se’K in the Mi’kmaq language) – into a stinking, toxic wasteland. It gives voice to people whose well-being, health, homes, water, air, businesses have been affected by the mill’s effluent and emissions, and to people whose livelihoods have depended on the pulp mill.

This compelling book is a rich tapestry of story-telling, of great interest to everyone who is concerned about how we can start to renegotiate the relationship between the economy, jobs, and profits on one hand, and human well-being, health, and a healthy environment on the other.

The Mill tells a local story with global relevance and appeal. It is a story of corporate capture of governments and regulatory agencies that citizens have been protesting and struggling to reverse for the last half century … and even longer.

About the author: Joan Baxter is a journalist, science writer, anthropologist and an award-winning author. She has written seven books, authored many media and research reports on international development and foreign investment, and reported for the BBC World Service and contributed to many other media, including the CBC, Le Monde Diplomatique, Toronto Star, The Globe and Mail, The Chronicle Herald, The Coast.

In the media …

CTV Live At Five, November 27, 2017, Host Kelly Linehan interviews Joan Baxter about “The Mill – Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest.”

The News (New Glasgow), November 23, 2017, “Author releases book offering critical look at pulp mill,”by Sam MacDonald

If there was anyone who didn’t agree with Baxter and her position, they did not speak up that night. The Tuesday evening event had an air of utter solidarity, with singer and activist Dave Gunning, a member of the Clean the Mill Group, opening with music that was a propos to the theme of the book.

Baxter admitted she was surprised that nobody spoke out against her writing and assertions, saying, “I was talking to a friendly audience and I was a little surprised that I didn’t hear any differing opinions.

“I understand that this can be a sensitive topic – livelihoods depend on the mill. I would have been happy to engage people, if they read the book.”

Author interviewed on The Rick Howe Show, News 95.7, Halifax, Nova Scotia November 23, 2017, 9 – 10 AM, at 39 minutes 42 seconds

“The Mill – Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest” is available in selected bookstores, and also online at:

For more information / media inquiries:

Joan Baxter: Themillthebook@gmail.com, joanbaxter.ca

Lesley Choyce, Pottersfield Press: lchoyce@ns.sympatico

Upcoming events

Author book signing “The Mill: Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest”, Saturday, November 25, 2017: 12 noon – 1:30 PM, Indigo Chapters bookstore, 41 Mic Mac Boulevard, Dartmouth, Nova Scotia

Author book signing “The Mill: Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest”, Saturday, December 2, 2017: 12 noon – 1:30 PM, Coles Bookstore, Truro Mall, 245 Robie St, Truro, Nova Scotia

Author book signing “The Mill: Fifty Years of Pulp and Protest”, Saturday, December 2, 2017: 3 – 4:30 PM, Coles Bookstore, Highland Square Mall, 689 Westville Rd, New Glasgow, Nova Scotia (This event will not take place on December 2, 2017 … if it is rescheduled, I will keep you posted!)

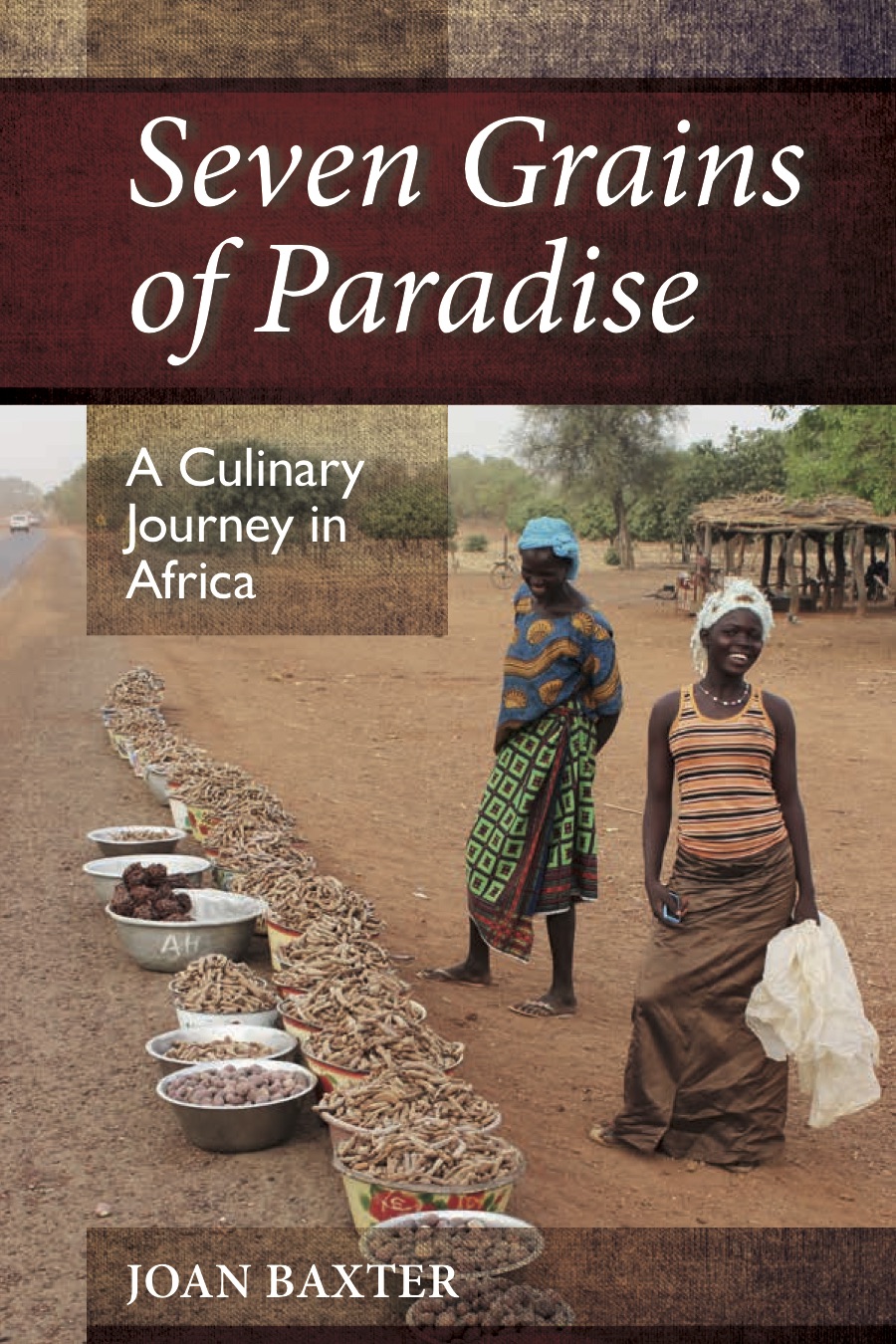

In her new book, “Seven Grains of Paradise,” Joan Baxter challenges many myths and explores the wealth of African food cultures and knowledge, foods and crops, and farming know-how.

In her new book, “Seven Grains of Paradise,” Joan Baxter challenges many myths and explores the wealth of African food cultures and knowledge, foods and crops, and farming know-how.

On a balmy, overcast August day, I stood at Port Joli Head in the

On a balmy, overcast August day, I stood at Port Joli Head in the

I wish I were writing to you under better circumstances, and not when you are at such a low point in your history, so badly abused by

I wish I were writing to you under better circumstances, and not when you are at such a low point in your history, so badly abused by

r more — perished in Belgian King Leopold’s Congo during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

r more — perished in Belgian King Leopold’s Congo during the late 1800s and early 1900s.

We were meeting under a thatch roof at the makeshift headquarters of Addax Bioenergy in northern Sierra Leone. Aminata Koroma, Social Liaison Officer for the company, was extolling for me the virtues of the project that was transforming great swaths of farmland, grassland and woodland around us into massive sugarcane plantations. Addax Bioenergy, part of the Addax & Oryx Group headed by Swiss billionaire Jean-Claude Gandur, had recently leased more than 50,000 hectares in the area, with the intention of processing the sugarcane to produce ethanol for export to Europe, where it would be used to fuel vehicles. Koroma was more than enthusiastic about the project, despite a good deal of local opposition among farming communities.

We were meeting under a thatch roof at the makeshift headquarters of Addax Bioenergy in northern Sierra Leone. Aminata Koroma, Social Liaison Officer for the company, was extolling for me the virtues of the project that was transforming great swaths of farmland, grassland and woodland around us into massive sugarcane plantations. Addax Bioenergy, part of the Addax & Oryx Group headed by Swiss billionaire Jean-Claude Gandur, had recently leased more than 50,000 hectares in the area, with the intention of processing the sugarcane to produce ethanol for export to Europe, where it would be used to fuel vehicles. Koroma was more than enthusiastic about the project, despite a good deal of local opposition among farming communities.