This article was first published by the Halifax Examiner on August 25, 2025.

Article summary:

• Over the lifetime of the Northern Pulp mill, Nova Scotia lost hundreds of millions of dollars because of incompetent, naive, and complicit governments.

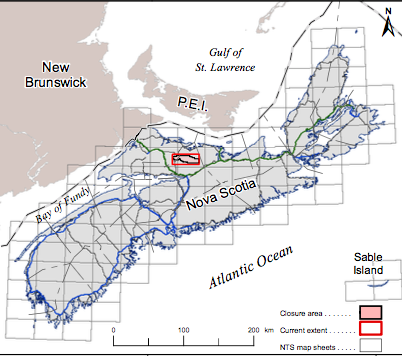

• As Northern Pulp’s billionaire Indonesian owners have opted not to build the new mill and instead allow the company to go into bankruptcy, 420,000 acres of Nova Scotia forest land are up for grabs.

• A shadowy company called Macer Forest Holdings has placed an under-valued bid of $104 million on the land.

• A Macer-affiliated company called Acadian Timber looks poised to log that land.

• One of Acadian’s board members, paid $56,000 annually, is Karen Oldfield, the interim president and CEO of Nova Scotia Health.

• Maurice Chiasson, a lawyer who represented the province in the Northern Pulp insolvency hearings, is now representing Macer Forest Holdings in the very same court process.

• As the government is mandated to protect 20% of the province and is far short of meeting that obligation, buying back the Northern Pulp land presents an inexpensive opportunity to meet that goal.

It was clear from the start of Northern Pulp’s insolvency case filed in the British Columbia Supreme Court six months after the Northern Pulp mill closed, that the outcome was never going to be good for Nova Scotia.

Spoiler alert: the outcome is not only not good, it’s downright bad.

Legal giveaways and concessions by successive generations of Nova Scotian governments to the various large foreign owners of the pulp mill meant Northern Pulp had all kinds of legal recourse to punish Nova Scotia for not amending the 2015 Boat Harbour Act, and not allowing the mill to continue to pump toxic effluent into Boat Harbour, which had despoiled the Pictou Landing First Nation estuary for half a century.

When Northern Pulp failed to come up with a viable new effluent treatment system that passed environmental muster by the deadline of 2020, the mill had to shut down.