This article, the first of a three-part series on passenger rail in Canada, was originally published by the Halifax Examiner. The introduction is here.

It’s a Friday morning, which means the Ocean – VIA Rail’s thrice-weekly passenger train to Montreal – is sitting on the tracks at the VIA station in Halifax, almost ready for boarding.

But I’m not here today to take the train; I’m here to talk trains with Tim Hayman.

Hayman is a board member of the citizen transportation advocacy group Transport Action Canada and president of its regional chapter, Transport Action Atlantic. He’s met me in the elegant and spacious VIA Rail station, a grandiose hall adjoining the once-grand Nova Scotian Hotel, now owned by Westin.

Both were built by Canadian National Railways in the late 1920s. CNR (now CN) was founded as a Crown corporation in 1919, bringing under one roof several railways previously owned by the government, and others the government acquired after they went bankrupt.

As Hayman and I speak, passengers trickle in with their luggage, ready to board the Ocean, scheduled to depart for Montreal at 1pm

At the Halifax VIA Rail station, three times a week the departure screen shows the Ocean train leaving for Montreal at 13h. Credit: Joan Baxter

Hayman tells me he wishes he were getting on the train, as he always does, no matter how many times he’s made the Ocean journey over the years.

And he’s made it a lot.

Hayman documents his many trips in a colourful and fascinating “Tim’s train travels” blog that tells tales – some of them harrowing – about the ups and downs, the joys and also the woes, the delays and major disruptions that are part of the experience of travelling a train as antiquated as the Ocean, and running on tracks where VIA trains have to cede priority to massive freight trains owned by CN, which owns the tracks.

Even with all the pitfalls Hayman details in his blog, he loves the Ocean.

And he is happy to count the ways.

“If you’re travelling between here and Quebec and Ontario, or even if you’re travelling within the region, I don’t think you could find a more comfortable and enjoyable way to travel,” Hayman says. “You see a lot of parts of the province you might otherwise not see. It’s some beautiful scenery.”

VIA Rail Ocean route. Credit: VIA Rail website

Slow and relaxing

“It’s relaxing. It’s a slow way to travel, but there’s something really valuable in that,” Hayman tells me. “You get an appreciation for the distances that you’ve covering, and it also kind of forces you to disconnect for a bit.” Although there is Wi-Fi in the service cars on the train, Hayman says, “There are lots of sections where you can’t get a cell signal or anything.”

“The service overall is excellent. I cannot say enough about the people that work on the trains here,” Hayman continues. “The last few years have been a testament to the quality of the crews on-board, especially when they had that chunk of time [during COVID] when they were all out of work and we didn’t have a train running.”

View from VIA Rail Ocean train in northern NB on tracks along the Bay of Chaleur, with the Gaspé Peninsula in the far distance. Cedit: Joan Baxter

Hayman adds:

You meet a lot of wonderful people on the train. That’s been one of the most enjoyable and rewarding things about it. I’m generally pretty introverted, not a super sociable person, but there’s something about the train environment where you’re in this space with a bunch of other people. And it’s a really good opportunity to just meet them, talk to them. There are lots of things to love about that.

A passion for trains

Hayman’s passion for trains began in his childhood when he watched them passing his home in Johnstown, a rural community on the St. Lawrence River just upstream from Brockville, Ontario. As a child, Hayman remembers playing with toy trains, like so many children through the ages, and watching “Thomas the Tank Engine” television shows, narrated by Ringo Starr and George Carlin.

He’s been riding on VIA Rail’s Ocean regularly since 2007, when he moved to Nova Scotia to study. He says one of the things that appealed to him about studying in eastern Canada was the chance to take the train back and forth.

He stayed on in Nova Scotia to do post-graduate studies, and then settled here.

So Hayman was in the province in 2012 when VIA Rail, a Crown corporation, dramatically slashed passenger rail services across the country.

Atlantic Canada was hit hard.

Casting doubt on the ‘future of train service’ in NS

“The Ocean went from six-day-a-week operation down to three days a week,” Hayman says. “It was at the same time that a number of these services across the country were cut back, related to budget cuts and a VIA Rail president at the time who clearly had a mandate to scale back quite a few of the operations, particularly long-distance services.”

At the time of the cuts, Marc Laliberté was VIA Rail’s president and CEO. He’d been appointed in 2009 by Stephen Harper’s transport minister John Baird, and in Laliberté’s view, the 2012 cuts he made “helped VIA Rail strengthen the foundations of our company for the coming years.”

VIA’s 2012 annual report boasted about the “rigorous cost management measures” that reduced government funding by more than $8 million over the previous year, and by more than $38 million since 2010.

“Rigorous cost management measures,” of course, translated in real English into VIA Rail passenger rail being cut to the bone.

Hayman says the “sudden and huge” reduction in service in 2012 “really brought the whole future of train service here into doubt.”

Round after round of cuts

The 2012 cut came 22 years after another “dramatic round of cuts” to VIA Rail under the government of Progressive Conservative Prime Minister Brian Mulroney.

In 1990, “more than half of the entire VIA network from coast to coast was cut in one fell swoop,” Hayman says. “And there had been a series of other kind of steady cuts to VIA through the 80s. But that was really the single, most draconian strike to the network.”

Hayman describes the effect it had on Nova Scotia and New Brunswick:

In the Maritimes here, we had the Ocean, the one bit of the network that’s stayed on long term. Up to that point you had all of these other services running to Sydney, and to Yarmouth, up through the valley, and in New Brunswick down to Saint John and Fredericton and all of these services as well. All of that got cut in a single day.

After that there were still two trains that remained from Halifax to Montreal, the Ocean and the Atlantic, [which had been operated by Canadian Pacific Railway before VIA Rail was created and took it over]. Both ran three times a week. The Atlantic was the train that ran from here to Moncton, and then ran down to Saint John and ran across through the northern part of Maine on its way to Montreal. When they cut the Atlantic, the Ocean went to six days a week.

Then in 1994, under the federal Liberal government of Jean Chrétien, the Atlantic was discontinued.

For the next 18 years, the Ocean ran six times a week, when it was reduced to just three weekly trips in 2012.

A short recent history of passenger rail in Canada

It wasn’t always like this, of course. There was a time in this fair land when train travel in Canada was one of the most reliable ways to get around the country, including rural and remote areas.

On the east coast of Canada, passenger rail was available in all four Atlantic provinces until 1969, when service in Prince Edward Island and Newfoundland ended.

The demise of regular and reliable passenger service in Canada is long and complex, as is the history of the railroad itself.

That history is blighted by colonialism and stolen Indigenous lands, exploitation, and racism. It is also wrapped up in “national dream” myths that the transcontinental Canadian Pacific railroad was built “to create a country,” when in fact it “was built for the purpose of making money for its shareholders and for no other purpose under the sun.”

All of this has been told in many books by many prominent Canadian literary figures. But that doesn’t explain what has happened in recent decades to the nation’s rail services, so a quick recap of that may be useful here.

Although there were many small rail companies across the country by the early 20th century, two corporations dominated freight and passenger rail for the next hundred years.

One was Canadian Pacific (CPR or CP), a private company incorporated in 1881 that – thanks to generous government subsidies – oversaw the building of the country’s first transcontinental railroad.

The other was Canadian National Railways, established as a Crown corporation in 1919, and then renamed Canadian National Railway (CN) in 1960. CN also owned ferry operations under its CN Marine subsidiary. In the 1970s and 80s, CN divested itself of its trucking, hotel, real estate and telecommunications companies, as well as Air Canada, which was then privatized in 1988.

Rails to roads

From the 1940s through the 1960s, rapidly expanding road networks and the use of private vehicles and trucks cut into rail use and revenues.

As Eric Schlosser notes in his landmark 2002 book, “Fast Food Nation,” private automobile use increased rapidly in the 1940s, partly because “driving seemed to cost much less than using public transport – an illusion created by the fact that the price of a new car did not include the price of building new roads.”

“Lobbyists from the oil, tire, and automobile industries, among others, persuaded state and federal agencies to assume that fundamental expense,” Schlosser writes. The rail companies had to lay and maintain track themselves, but big auto companies were not required to pay for the roads governments were building for the automobiles they were selling.

Schlosser continues:

The automobile industry, however, was not content simply to reap the benefits of government-subsidized road construction. It was determined to wipe out railway competition by whatever means necessary …

Schlosser describes how General Motors secretly began buying up tracks for trains and trolleys, and then completely dismantling them, ripping up tracks and tearing down overhead wires, and turning the routes into bus services, running GM buses.

The result was the destruction of America’s light rail network, and the “postwar reign of the automobile.”

Schlosser was writing specifically about the United States and its light rail network, but the shift from rail to road was also happening north of the border.

Rural areas abandoned

By the middle of the 20th century, passenger rail incomes in Canada had fallen dramatically, under pressure from road transportation and expanding air travel.

That meant big changes were coming to passenger rail service.

From the 1970s through the 1980s, thousands of rail lines were abandoned, many ones that once provided passengers rail service in rural areas.

Wayne Edgar grew up in Halifax, but now lives near Tatamagouche in northern Nova Scotia. Edgar’s father and grandfather both had long careers working for Canadian National when it still ran passenger trains. In an interview, he describes the loss of passenger rail service as “very sad” and “a terrible tragedy.”

“When I first came to live in Tatamagouche in 1970, the rail line between Oxford Junction and Pictou and New Glasgow was still functioning, going up one day and down the next,” Edgar says. “Then it slowly became less frequent, and then only once a week, until it just stopped altogether.”

“The decline of the railway, I think, was also part of the decline of rural communities and the focus on urbanization,” Edgar says.

VIA Rail is born and CN is sold off

According to a 2015 parliamentary background paper, in the 1970s, CN and CP were facing declining passenger revenue, and agreed to form a passenger service that would operate as a subsidiary of CN.

Then in 1977, the federal government created VIA Rail as a Crown corporation “in an attempt to avoid the complete disappearance of intercity passenger rail service.” VIA Rail was a subsidiary of CN, which was itself still a Crown corporation at that point.

In 1995, Jean Chrétien’s Liberal government privatized CN. Preparation for the privatization had already begun in 1992, under Brian Mulroney’s Progressive Conservative government, spearheaded by two former federal civil servants. However, the CN Commercialization Act wasn’t enacted until July 1995. It stipulated that no individual shareholder could own more than 15% of CN and that the company’s headquarters remain in Montreal, so that it would still be a Canadian company.

But many of the investors who snapped up CN shares – $2.25 billion worth – were American private equity firms. The largest shareholder was the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation Trust, with 14.2% interest. After the Gates divorced in 2021, Melinda French Gates became one of the largest single CN shareholders.

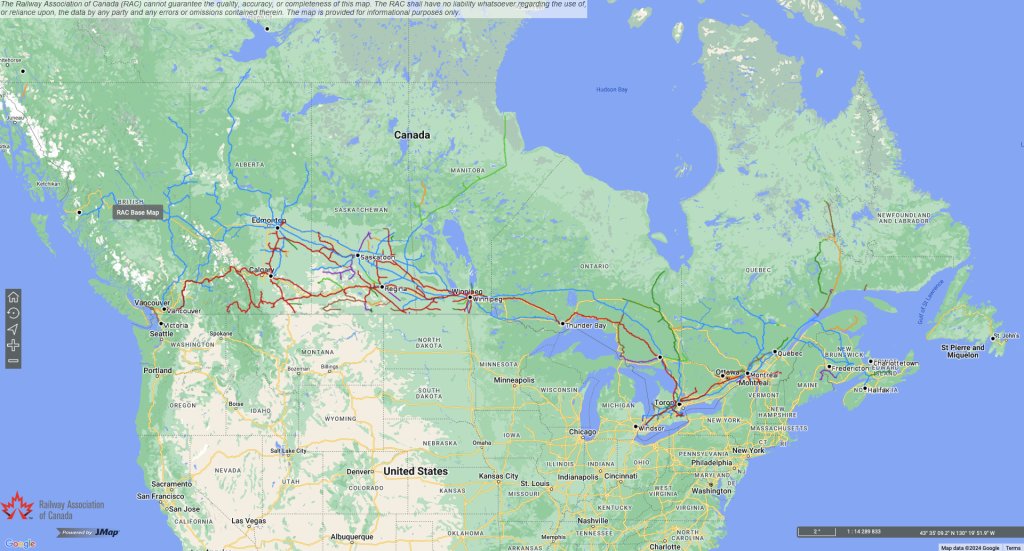

Today, French Gates remains one of the largest shareholders of Canada’s largest railway. CN describes itself as a “leading North American transportation and logistics company” with 23,000 employees, which carries $250 billion worth of freight every year, across its 32,000 kilometres of track stretching from Nova Scotia to British Columbia, and south into the United States.

Canadian Pacific no longer exists. In April 2023, CP merged with Kansas City Southern to form CPKC, which carries freight over its 32,000 kilometres of track through Canada, the United States and Mexico. CPKC owns about 11,500 kilometres of track in Canada.

Neither CN nor CPKC operate regular passenger service, although through a subsidiary CPKC does run a seasonal, luxury (read: very, very expensive) excursion train – the Rocky Mountaineer – between Vancouver and Calgary.

Both of these corporate behemoths – CN and CPKC – own most of the rail tracks in Canada.

Railway Association of Canada atlas of existing rail lines in Canada. Credit: Railway Association of Canada

Herein lies an immense problem for VIA Rail.

The Crown corporation was created with no trains or train stations, and with no tracks of its own, so it had to “negotiate operating agreements with CNR and CPR,” which of course had priority on those rails for their freight trains.

In addition, much of the equipment VIA eventually acquired was “outdated and obsolete.”

And those were just some of VIA’s problems.

VIA at the mercy of politicians

VIA Rail has a federal mandate, to provide “national passenger rail services on behalf of the Government of Canada, offering intercity rail services and ensuring rail transportation services to regional and remote communities.”

It does what it can.

Today, VIA Rail carries 3.3 million passengers, has 3,348 employees, serves 400+ communities, and has $335.5 million in revenue per year.

But the Crown corporation faces enormous obstacles. VIA Rail was created by order in council and still has no “enabling legislation. That means it has “no borrowing authority,” and only “limited autonomy.”

In other words, VIA Rail operates completely at the whim of the federal government, dependent entirely on its own revenues and any funding that parliament agrees to provide to make up for deficits.

So it should come as no surprise that VIA Rail trains suffer long delays and occasional fiascos, as the Crown corporation struggles against big odds to maintain passenger rail service using antiquated equipment on tracks that it doesn’t own.

Some ‘dramatic’ things do happen

Which brings me back to the VIA Rail station in Halifax, where Hayman is telling me that as much as he loves the Ocean, he’s also had some “dramatic” experiences on the train.

The most recent of these was at Christmas in 2023, when, Hayman says, “the trains ran pretty well.” There was one exception, which happened to be on the day he was travelling.

“It was one of those trips when just about everything that could go wrong, did go wrong,” Hayman explains. First, the eastbound train was late leaving Montreal because of a late connection, and then a locomotive died, and the Ocean had to go back to Montreal to get a new locomotive.

“So they were really, really late,” Hayman says. The train, which normally departs Montreal at 7pm, finally departed at 3am. The saga continues:

Then they were in rural Quebec and hit some farm equipment at one of these little private farm crossings, which damaged the lead locomotive, ruptured the fuel tank. So they were stuck there for a while to clean things up, and they had to borrow an engine from CN to get the train the rest of the way here. So that train, when it got to Halifax, was about 23 hours late. I was supposed to be leaving on the next train going out from here, at 1pm on Sunday. But it didn’t leave until 11:30pm … We got as far as Campbellton, and the [borrowed] CN locomotive that was leading us died. And they had no other locomotives anywhere nearby that could be brought in. So we got on buses in Campbellton for the rest of the way to Montreal, and got in the next day at 3:30am.

Hayman smiles, and adds, “It wasn’t as dramatic as precious years,” such as the “2022 Christmas chaos” he describes in his blog.

With a chuckle, Hayman says, “I noticed a few of the crew members on there this year who had been on my trip last year at Christmas time. And one of them said to me, ‘We really need to stop letting you on this train. It’s not working out well.’”

But, of course, the problems VIA struggles have nothing to do with passengers or crew, or indeed with VIA’s management.

VIA Rail on a ‘shoestring budget’

Rather, Hayman says, “The problem for VIA has always been that they’ve been asked to do a lot on a shoestring budget, and there is a lot of pressure on VIA to demonstrate better cost recovery, and reducing their required subsidy.”

He says it is impossible for VIA Rail to maximize revenue from the Ocean when it runs only three times a week. As a result, VIA has been trying to find revenue anyway it can, putting it in what Hayman calls a “weird spot,” marketing itself and its sleeper class as a kind of land cruise service, rather than providing a frequent, affordable, and reliable means of transport for people travelling between Halifax and Montreal.

VIA’s flagship Toronto – Vancouver train, the Canadian, now offers a very expensive “prestige” class, appealing to well-heeled tourists and people for whom time and money are not in short supply.

Compared with that, the Ocean looks neglected and dilapidated – but it is still not inexpensive to ride. At Christmas 2023, a return trip with a sleeper cost over $1,000.

‘Slower and slower and slower’

In the 17 years he’s been taking VIA trains between Halifax and Montreal, Hayman says he’s seen many “steps down” in the overall service on the Ocean.

Not only does the train run only three times a week, but Hayman says it has become “slower and slower and slower.”

“That’s been really noticeable, and a lot of it is due to the condition of the track through northern New Brunswick,” Hayman says. “CN owns the track, but they run virtually no freight over that in the section between Miramichi and Bathurst.”

There is a long stretch of the track where the maximum speed for the train is just 30 miles per hour (48 kilometres per hour), Hayman says.

Unlike the VIA’s Toronto-Vancouver train, the Ocean no longer has a car where passengers can go to enjoy a panoramic view of the countryside they are riding through.

Hayman says that the “park” or dome car that used to be at the end of the train is now parked permanently, and has been since the Ocean resumed operations after COVID restrictions eased in 2021. He explains that there is a loop track around the Haltherm container terminal to the south of the Halifax VIA station, where the Ocean used to turn around. Haltherm wanted that space for more containers. So VIA lost its turnaround loop and had to remove the dome car at the end of the train.

VIA has yet to replace it with another panorama car that could go mid-train.

But that’s a minor issue compared with the age of the trains themselves.

Pressing issue is ancient equipment

Says Hayman, “The other really big thing … the really pressing issue at the moment is the overall state of the equipment.” He explains that the Ocean runs a “mix of two types of equipment.”

Some of it – the “Renaissance” equipment that VIA purchased in 2003 – is second-hand, originally built in the 1990s in the United Kingdom.

“VIA got it at a bargain price because it was all built – and some of the cars were partially built and not completed – intended for the overnight service that was going gto run through the English Channel tunnel, and that just never happened,” Hayman says.

Because the cars weren’t meant for the Canadian climate, there have been many issues with reliability over the years, and lots of modifications required. Says Hayman:

They’ve done a commendable job of keeping them working. But it’s getting harder and harder as time goes on, especially because they weren’t built to sustain the kind of operating environment that they run under. So right now, there’s only a fairly small portion of that fleet still operating.

Then there are the really old “HEB 1” [Head End Power] cars, which date back to the 1950s and even the 1940s, which VIA Rail obtained from Canadian Pacific.

“They’re still in pretty admirable shape given their age. They were built to last, but they’re hitting 70 years old,” Hayman says. “And the reality is … they were not ever intended to run that kind of lifespan. VIA has got a lot of years out of them by progressively rebuilding and rebuilding and rebuilding them. But they’ve discovered in the last few years that a lot of those cars are starting to get cracking in the sills and frames.”

Hayman points out that in addition to these obvious problems with the antiquated cars, they are also not equipped for “modern accessibility requirements” and they desperately need to be replaced.

And soon.

But train replacement isn’t going to happen “soon.”

“VIA is in the process of trying to move ahead with new equipment procurement,” Hayman says. But, he notes, “It takes time if you’re going to build new equipment, especially if it’s going to be purpose-built for long-distance services, and provide the kind of amenities that you want for these trains. You’re looking at least five to six years from order to actually having any trains in operation, and then a few years beyond that to have the full fleet in operation.”

And there is still no federal funding for the replacement of the Ocean fleet.

If there is funding in the 2024 spring federal budget, VIA can go ahead with the tender and then hopefully the order that would keep the Ocean running beyond the next few years, something we’ll look at later in this series.

A ‘dream scenario’ for passenger rail

In the meantime, Hayman says his “dream scenario” for passenger rail service in Atlantic Canada looks like this:

First, we would have a version of the Ocean as a long-distance train into Montreal running every day. That would be the spine of the network of regional trains that would feed into it. You’d also have additional daily trains running at commuter-oriented times between here and Moncton, from Moncton to St. John.

Hayman thinks this should also be the vision for the rest of Canada, with backbone long-distance passenger trains, and smaller corridors with some level of daily services. As for Nova Scotia, his future dream scenario looks a lot like days of yore:

I would like to see something that would look an awful lot like the network before 1990, with that central line running out of Halifax with the connection to the rest of the country, but with lines splitting off from Truro through to Cape Breton and from here down through the valley to Yarmouth, and also up to Tatamagouche [I think he said that for my sake, to be honest, as I had complained about the total lack of public transport between Halifax and Tatamagouche on the north shore].

Hayman says that there are a lot of abandoned rail lines that have not yet been converted to recreational trails, which could be restored. But he’s realistic about the challenges involved in restoring rail networks.

“It’s really hard to establish new corridors for any dedicated rights of way, whether that’s for commuter rail or intercity passenger rail or for freight traffic,” Hayman says.

Some municipalities in the country have “done really well” keeping corridors where rail lines have been abandoned, looking forward to the day that they might use them again, Hayman says.

“I don’t think there has ever been that progressive look in Nova Scotia,” he adds. Instead, the idea was that when trains stopped running, that marked “the end of an era.”

“A lot of short-sighted decisions have been made over time,” Hayman tells me.

Public passenger rail flourishing in other countries

Still, Hayman is convinced passenger rail is the future.

“It plays a really important role in the overall transportation picture,” Hayman says. “Specific advantages are that passenger rail can be the most environmentally friendly and sustainable form of transportation, if the trains are modern and efficient.” It can also be the most accessible.

And if anyone has any doubts, Hayman says all they have to do is look around the world to Europe and Asia and other parts of the world where trains are fast, affordable, efficient, and well funded by governments as a crucial public service.

Canada may be lagging behind, Hayman says, but there is no reason that can’t change.

Next in the trilogy: Trying to give VIA Rail a chance