BY Joan Baxter

July 14, 2017

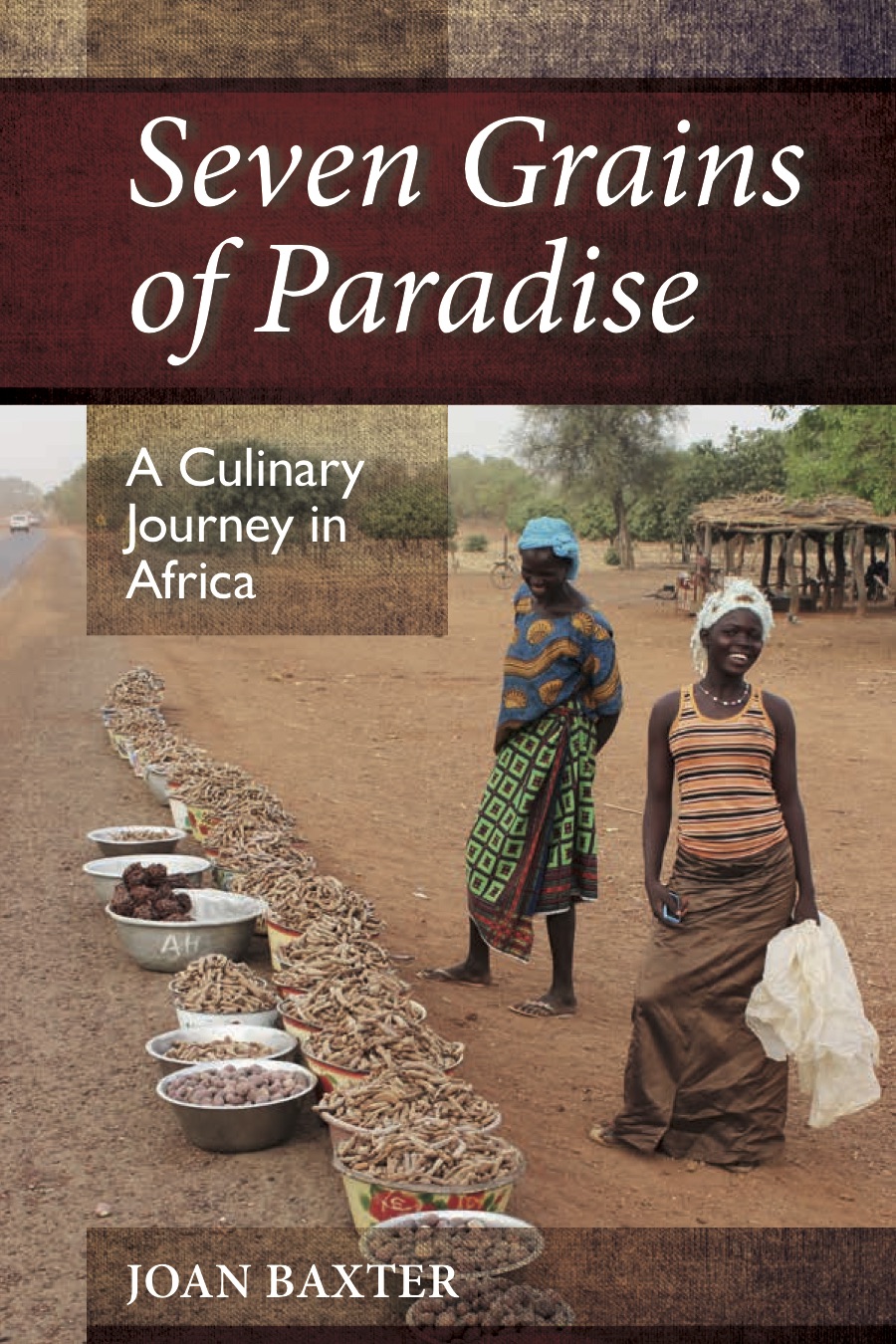

(This article is the second of two adapted excerpts from Seven Grains of Paradise: A Culinary Journey in Africa, available in print and Kindle edition at Amazon.ca and as an e-pub from Amazon.com and Kobo, and in print from Nimbus.)

At the beginning of the 1960s, when many African countries were becoming independent nations, freeing themselves one after another from the colonial powers, the continent was more than able to feed itself. Until 1970, it was even exporting food, more than a million tonnes a year.

At the beginning of the 1960s, when many African countries were becoming independent nations, freeing themselves one after another from the colonial powers, the continent was more than able to feed itself. Until 1970, it was even exporting food, more than a million tonnes a year.

Today, after more than half a century of foreign development assistance and food aid, as well as decades of economic development doctrines from the World Bank Group, International Monetary Fund, foreign “donors,” and most recently, billionaire philanthropists, the continent imports a quarter of its food.

This lands us right in the middle of the kitchen staring into the eyes of the big elephant of a question that is sitting there: Why has Africa become synonymous in many people’s minds with malnutrition, famine and hunger, and not feted for nutritious foods, diverse farms and wonderful cuisines?

Some of the causes for periodic humanitarian crises and rural poverty are evident. Africa has suffered enormously from political instability and turbulence; in the half century before 2004, it saw 186 coups and 26 major wars, which produced 16 million refugees.

Farmers need stability and security to grow food, and also a voice that is heard and respected by political elites, and in much of sub-Sahara Africa they have had neither. Rapidly changing demographics have put additional strains on land, resources and social services; the population of the continent more than doubled between 1975 and 2005.

The main road linking Kailahun, in eastern Sierra Leone, an important agricultural region, with the capital, Freetown. (photo: Joan Baxter)

Governments have tended to ignore rural areas, which suffer from poor roads, a lack of health and education facilities and other infrastructure that would make rural living more appealing. There is also the unfair competition that local farmers face from subsidized produce from abroad that is often dumped on the continent.

Rather than the respect that farming deserves as the profession that nourishes nations, it is often seen as a desperate, last-resort choice in life. Today, children in Sierra Leone may be warned that if they don’t work hard and do well at school, they will wind up being a farmer, as if it’s the worst thing in the world rather than the respected, fulfilling and noble way to make a living by feeding the world, which it should and could be. Unfortunately, this is the same the world over.

Stereotypes born of ignorance….

The myths and misconceptions about African farming, foods and food cultures certainly come in all shades of bleak and even ridiculous and pathetic. In 2012, a jet-setting British national and CEO of a gold prospecting company with interests in Liberia, was asked by an online management publication what his worst travelling experience was.

He responded thus. “On one of my first trips with my business partner, we broke down in the middle of the jungle [in Liberia]. We walked into a village and waited while the villagers decided what to do with us — were they going to put us in a pot and eat us? But they made us welcome and offered a bed on their mouse-infested floor in a mud hut. I always find these experiences entertaining.”

This is what he had to say about the food his hosts in Liberia offered him. “The local dish is rice and crushed fish bones — horrendous. I stick to Dairylea slices and Coke.”

It could be said that what is “horrendous” about this incident is that a foreign national in Liberia looking to mine its gold wealth is so painfully ignorant about its wealth of foods and dishes. Not to mention how ludicrous it is that anyone could think sugary soft drinks and industrially produced cheese-like slices are superior to a healthy meal of rice and fish.

…and a colonial legacy

But such comments speak volumes about the ludicrous and disparaging stereotypes about food and food cultures in Africa. Many seem to have been shaped by a historical or media reports about Africa written primarily by Europeans. And many of those, in turn, are imbued with an inflated sense of superiority or written by individuals suffering from terminal Hubris eurocentrisis (okay, I made that up, but I maintain that it is a verifiable condition).

School curricula around the world, with some notable and fairly recent exceptions in Afrocentric programs, have given short shrift or none at all to Africa’s complex history, cultures, rich oral traditions and wisdom captured in proverbs and fables, to its literary, artistic, scholarly and musical accomplishments and its immense contribution to human development.

Nor has enough attention been paid to the amount of wealth that African slaves created for white plantation owners and economies in the Americas with their forced and free toil in rice, cotton and sugarcane fields. Since this African agricultural prowess has been so neglected, it’s not really surprising that school curricula have also failed quite spectacularly to give the rich heritage of African crops, foods and food cultures its due.

In lieu of much meaningful education about Africa, much of the “knowledge” floating around out there about the continent has been brought to us by Disney and Hollywood, by charities seeking funds, and even tired old colonial biases and misconceptions that have been handed down through generations. Much of it falls into the category of myth, half-truth, sometimes even spurious fiction.

Dispelling myths, half-truths, and spurious fiction

Africa is the most diverse continent on the planet. It boasts all manner of contrasting ecosystem, from snow-capped mountains (at least until climate change began their meltdown) to inhumanly hot salt flats more than half a kilometre below sea level and surrounded by a lake of soda. In fact, these two spectacularly different landscapes are found in just one African country — Kenya. Parts of the continent are covered by rainforests; much of it is desert. Some of Africa is mountainous. Some is flat. Some is merely hilly.

In the highlands of northwestern Cameroon, family farms are agro-ecological models of sustainable agriculture, with annual crops mixed with trees in agroforestry plots (photo: Joan Baxter)

Some believe it is covered almost entirely by savannahs on which lions and elephants roam unchecked. Some believe that nearly everyone on the continent is starving and living in a refugee camp. Others believe you can’t walk down a road in Africa without meeting a rebel soldier brandishing a sub-machine gun or a machete, braying for blood.

None of this is really surprising, given the way Africa is portrayed in the media, and the factoids about Africa that many children in Europe and North America have been served in their early years. Odd notions about the continent are drilled into young heads by films or cartoons and a host of aid agencies intent on drumming up support for their work overseas with fund-raising campaigns featuring stereotypes and sometimes horrific imagery that lasso the compassion and good intentions of adults and children far away.

Out of this emerges the implausible but often unquestioned myth that no one in Africa could possibly survive without Western help and food aid, as if life in the cradle of humankind did not tick along for millennia, and indeed give rise to the species to which we all belong.

Being ultra-rich doesn’t mean knowing the solutions

This notion has in turn spawned a corollary myth that famine strikes because people don’t know how to farm and are sitting there twiddling their thumbs until a Western youngster, missionary, economist or volunteer aid worker comes to “teach” them how to coax crops out of the soil, with funding from an “ultra-high-net-worth-individual” — UHNWI for short — dressed up as a philanthropist who has never grown so much as a bean.

“Confidence” brand “farm fresh” eggs from India for sale in remote markets in Sierra Leone (photo: Joan Baxter)

Rarely examined by mainstream media are the real causes of major famines, which are often political, or related to climate change that Africa has not been causing, and sometimes even because of misguided agricultural development “aid” and advice from misguided or misinformed foreigners.

But the stereotypes, as wrong as they are, are being used to justify the takeover of Africa’s food and farms by global corporations through multi-billion-dollar initiatives, heavily backed by and benefitting multinational corporations — from the G7/G8 New Alliance for Food Security and Nutrition to the Alliance for a Green Revolution in Africa (AGRA), as well as an onslaught of foreign investors and funds of all stripes seeking great swaths of Africa’s arable land as a new asset class, a which the NGO GRAIN calls a “global landgrab.”

Ironically, just as Africa’s foods and agro-ecological farming are being threatened by the push for industrial corporate agriculture on the continent, African chefs, cooks, farmers and activists are working hard to promote its diverse and rich cuisines around the world. Let’s hope they succeed before the continent’s crops, foods and food cultures are overtaken by the industrial food system that is garrotting the globe.