This article first appeared in the Halifax Examiner on March 7, 2019. As decision-day approaches on Northern Pulp’s proposal for a new effluent treatment facility that would be constructed very close to the Canso Chemicals site, which is heavily contaminated with mercury, I decided to republish the article here.

Canso Chemicals hasn’t produced any chemicals for 29 years, but — contrary to what I wrote in the Halifax Examiner in “Northern Pulp’s environmental documents: missing mercury, a pulp mill that never was, and oodles of contradictions” — the company lives on.

Sort of.

For two decades Canso Chemicals produced chlorine for the pulping process at a site adjacent to the pulp mill on Abercrombie Point in Pictou County, but when new pulp and paper effluent regulations came into effect in 1992, the mill switched to chlorine dioxide. No longer needed, the chemical plant was closed.

A Google search for “Canso Chemicals” turns up an address (Granton Abercrombie Road, New Glasgow, NS) and a phone number, which I called. Although the Google result states that it is “permanently closed,” someone did answer the phone with the words, “Canso Chemicals.” When I introduced myself, he said he could not make any comment, but would try to find someone who could answer my questions about the company. He took my number. I haven’t had a return call.

Canso Chemicals is also an “active” company on the Nova Scotia Registry of Joint Stocks. Its listed directors are: Curtis Richards of Cleveland, Tennessee; Pierre Ducharme of Becancour, Quebec (also listed as president); Choong Wei Tan of Richmond, BC (who is also a director of Northern Resources Nova Scotia Corporation, parent to Northern Pulp), and Seymore Thomas Dewtie of Abercrombie, NS. Canso Chemicals’ registered office and mailing address are the same as McInnes Cooper law offices in Halifax.

Canso Chemicals is an entity of the Olin Corporation, a “leading U.S. manufacturer of ammunition” and global supplier of chemicals. No stranger to Canada, the Olin Corporation’s Winchester Division has won numerous tenders to supply armaments to the federal government, and in 2009 won a contract to sell $420,313 worth of guns to the federal penitentiary in Dorchester, NB.

For many years, the John M. Olin Foundation used “profits from the Olin chemical and munitions fortune” to channel millions of dollars into right-wing think tanks and astroturf groups promoting conservative programs and causes in the United States.

Canso Chemicals’ relationship to the Olin Corporation explains the presence of Olin managers on the Canso Chemicals board of directors: Pierre Ducharme is manager for Olin Canada ULC, and Curtis Richards is Vice President of Environment, Health & Safety for the Olin Corporation in the US.

But Canso Chemicals’ relationship with the Olin Corporation does nothing to explain why the company still exists, and why it still owns 23 acres of land on Abercrombie Point on the site of a former plant that has not produced chemicals for the pulping process since 1992.

According to the Northern Pulp document (Section 8), p 165, submitted to the province for the environmental assessment process in February 2019:

The former Canso Chemicals plant is located on the adjacent property south of the NPNS [Northern Pulp Nova Scotia] facility industrial site. This adjacent operation was discontinued in the 1990s, but continues to serve as a distribution facility for NaOH [caustic soda].

In 2000, Dillon Consulting submitted a report entitled “Canso Chemicals Site Decommissioning Final Report” to the general manager of Canso Chemicals Limited, and cc’ed to Pioneer Chemicals Limited. The report says that Canso Chemicals had operated its chlor-alkali plant on Abercrombie Point for two decades, producing chlorine and caustic soda for the pulping process.

To do that, it needed mercury, and lots of it.

“We didn’t come here … to poison people”

Even before it opened in 1970, people in Pictou County were concerned about the possibility of mercury pollution from the Canso Chemicals plant. This was a time when the media were reporting widely on the debilitating effects of Minamata disease of the central nervous system, caused by methyl mercury pollution.

In April 1970, Ferguson MacKay sent a telegram to then Fisheries Minister Jack Davis highlighting the risks:

On behalf of the Committee for the Control of Pollution in the Northumberland Strait area of Pictou County, we are protesting the opening of the Canso Chemicals Limited plant at Abercrombie which is scheduled to go into operation within a few days. We are afraid of mercury pollution in the Northumberland Strait as a result of the operations and of the devastating results[;] we would request that the plant be prevented from going into operation until these matters have been investigated.

In response, Canso Chemicals’ Jack Pink assured the community:

We didn’t come here … to poison people … [we came] just to be an industry, employ people, and perform a useful service. This plant was designed and set up as the most modern of its kind for its size in the country but this mercury waste problem blew up only a short time ago and nobody had heard of it until then.

And:

The actual waste of mercury is minimal. Mercury is an expensive metal so every new plant is built a little better than the last one for the good reason of saving costs.

The New Glasgow News reported on April 29, 1970 that representatives of the provincial government’s Water Resource Commission had met with Canso Chemicals officials, and told them they would have to ensure that there would be only negligible mercury loss from its new plant. The company gave its assurance that it would take steps to comply.

Mysterious losses of lots of mercury

Whatever steps Canso Chemicals took to prevent mercury loss, those steps clearly didn’t work. In 1977, the Canadian Press reported that there had been “mysterious losses of large amounts of mercury” from the plant. Since the company had begun reporting to the federal environment department in 1972, Canso Chemicals reported “unaccounted mercury losses” that averaged several tons a year, with a peak in 1975, when five tons were lost.

It wasn’t until the plant stopped production in 1992, and the decommissioning of the plant began, that the mystery of the missing mercury was solved. According to the 2000 Dillon decommissioning report, equipment failures in the plant’s cell room from 1973 to 1975 resulted in “high mercury consumption and mercury was lost to the floor.”

Jill Graham-Scanlan, president of the citizens’ group Friends of the Northumberland Strait, whose father worked at Canso Chemicals, recalls her own working experience in the plant.

I worked there as a summer student while in university for a couple of years. One of my tasks was to vacuum mercury in the basement, under the cells, so I can certainly attest to the presence of mercury!

After it closed its plant, Canso Chemicals submitted a site remedial plan to the Nova Scotia Department of Environment. Remedial activities undertaken between 1992 and 1996 included finding mercury-contaminated soil under and around the Canso Chemicals plant, as well as materials collected in structures that were demolished; those items were to be disposed of in a “secure landfill” near the southern corner of the defunct plant.

Later, when the footings of the buildings were removed in 1999, “elemental mercury was identified in the bedrock,” deep underneath the former cell room and brine basement. Those mercury deposits could not be removed because of the risk of extending the contamination and because of their depth. As I reported previously for the Halifax Examiner, the mercury contamination is eight metres deep, five metres below the water table, and “there is potential for it to dissolve into groundwater and migrate towards Pictou Harbour.” According to the Dillon decommissioning report:

…the receptor of the mercury-impacted groundwater is expected to be Pictou Harbour, and the plume is expected to eventually discharge to the harbour approximately 700 m northwest of the former cell room … both water quality and sediment quality could be affected …

If there is any good news here, it is that the mercury plume may not reach Pictou Harbour for 200 years.

But that doesn’t mean the mercury isn’t a serious and constant concern. The provincial government has been doing annual mercury monitoring at the former Canso Chemical site for at least 20 years.

And, as reported previously, the site being monitored for mercury is “next to the site of the proposed Northern Pulp effluent treatment plant.”

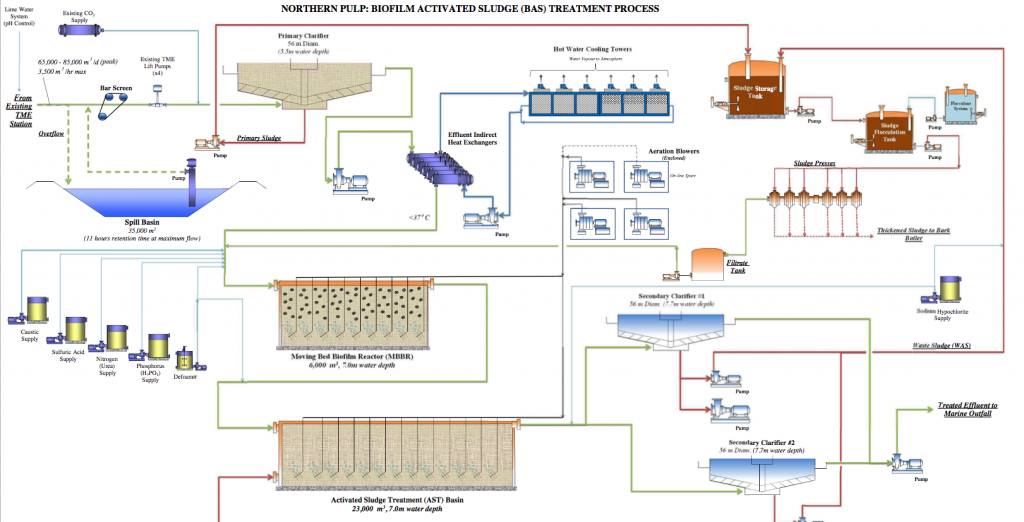

Northern Pulp does not mention mercury contamination in the documents it submitted in February 2019 for the provincial environmental assessment of its replacement effluent treatment facility, despite the proximity of the proposed treatment plant and basins to the mercury-contaminated bedrock and landfill on the Canso Chemicals site. Some of the treatment basins proposed have depths of over seven metres.

An email to Nova Scotia Environment with questions about the nature of the mercury monitoring, where that monitoring is being conducted, whether the monitoring includes the landfill where contaminated materials were deposited in the 1990s, and whether Canso Chemicals pays for the monitoring, has not been answered.

The site does not show up as one of Nova Scotia’s contaminated project sites.

Who owns the mercury problem?

Given that the mercury problem won’t be going away, monitoring will have to continue for many decades, even centuries. It is not clear who will pay the costs of the monitoring, or for more clean-up, should it be required — if the owners of Canso Chemicals are liable for these costs, or if Nova Scotians could wind up on the hook for them, as they are for the remediation of Boat Harbour.

The ownership of Canso Chemicals has never been widely publicized.

According to an unpublished report from 1970, the company was formed in 1968 by Canadian Industries Limited (CIL), Scott Maritimes (the first owner of the Pictou County pulp mill), Nova Scotia Pulp Ltd. at Port Hawkesbury.

In 1988, CIL morphed into ICI Canada. At some point, Olin came into the picture. Olin is a massive corporation that employs “6,500 professionals in more than 20 countries with customers in nearly 100 countries across the globe.” Today, Olin owns half of Canso Chemicals.

In its 2017 annual report, Olin reports that Northern Pulp, which it cryptically notes is “Pioneer related,” owns the other half of Canso Chemicals.

Olin’s 2018 filings to the US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) show that among its nearly 100 subsidiaries is one called “Pioneer Companies, LLC,” but there is no explanation of how Pioneer is related to Northern Pulp.

Northern Pulp is part of the Paper Excellence Group, which in turn is part of the corporate empire of the multi-billionaire Widjaja family of Indonesia, the Sinar Mas “brand of companies, active in 6 business pillars: Pulp & Paper, Agri-business & Food, Financial Services, Real Estate, Communications & Technology and in Energy & Infrastructure.”

Northern Pulp certainly doesn’t advertise its partial ownership of Canso Chemicals. I could find no mention of it on the Paper Excellence / Northern Pulp website.

A Facebook page for Canso Chemicals has been moribund since 2016.

Manta, a website documenting small businesses in America, describes Canso Chemicals Limited as a “privately held company in New Glasgow, NS,” and a “Single Location business” that can be categorized under “Special Warehousing and Storage.” According to Manta, “current estimates” show Canso Chemicals has annual revenue of $296,220 and a staff of “approximately 3.”

It is difficult to imagine that the two giant corporate behemoths that are ultimately its owners, Sinar Mas and Olin Corporation, can have much interest in such a tiny remnant of a company, which today employs three people and produces nothing at all.

So why does Canso Chemicals still exist?

Is it somehow more advantageous to keep the company in operation, at least nominally, so as to delay or avoid confronting the environmental liability of the mercury contamination on the land that Canso Chemicals owns?

Or is it possible — as impossible as it seems — that the Canso Chemicals site provides such an ideal caustic soda shipping and receiving facility that it is worthwhile for its owners to keep the company going?

But most importantly, has Canso Chemicals ensured that the mercury contamination on its land is a safe distance from Northern Pulp’s proposed replacement effluent treatment facility on Abercrombie Point?

Those are the questions I wanted to ask when I rang Canso Chemicals yesterday and left my number, hoping to hear back from someone who could answer them.

So far, I’ve had no call back from Canso Chemicals, no reply from Nova Scotia Environment to my email yesterday, and no answer to questions I asked a spokesperson at Olin Canada.

I am still waiting.

Update: Olin Canada sent the following statement after publication:

In 2007, Olin acquired the assets of PCI Canada ULC, which included the Canso terminal. The Canso terminal is used to deliver products to our Nova Scotia customer base. The current proposal does not include excavation near the landfill. As a Responsible Care® company we actively work with regulators in Canada to drive environmental and safety excellence throughout all of our operations. The safety of our employees, the community, and our environment is always our top priority.

One Comment, RSS