This is the third in a series of four articles on the 21st-century push for mining and quarrying in Nova Scotia on Canada’s Atlantic coast. Earlier versions of articles in this series appeared in May and June 2018 in the Halifax Examiner and the Cape Breton Spectator. (I am pleased to say that this series of four articles has been shortlisted for an Atlantic Journalism Award in Excellence in Digital Journalism: Enterprise/Longform.)

Part 3. Gold in the hills or clean water in the rivers? Citizens take on government geologists in northern Nova Scotia

The news broke in November 2017 on the front page of the free monthly community paper, The Tatamagouche Light, in an article written by Raissa Tetanish under the headline “Gold in the hills?”

“The hills” are the Eastern Cobequid Highlands in northern Nova Scotia, a mostly forested area of 30,000 hectares (74,132 acres), stretching from the Wentworth ski hill to Earltown.[1]

Tetanish reported that, not only did geologists from the provincial Department of Natural Resources (DNR) think there was gold in the Cobequid Hills, they had been prospecting there for six years. And now, reported Tetanish, DNR was preparing to invite mining companies from around the world to come and do more advanced exploration.

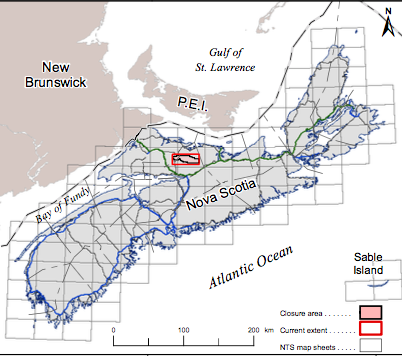

Screenshot taken from DNR geological map showing enclosure area slated for gold exploration in the Cobequid Highlands in Nova Scotia.

In 2016, the government had closed the area to any other prospecting while DNR geologists did their own hunting for gold. About half the enclosure area was the French River watershed, which supplies the village of Tatamagouche its drinking water. Concerns about the water supply aside, the geologists were “enthused” by what they’d found and “optimistic for the future,” reported Tetanish.

The article explained that there were plans to hold an “open house” to inform citizens about the findings, and the geologists said they would be promoting the “opportunity” at the next Prospectors and Developers Association of Canada (PDAC) convention, which would be held in Toronto in March 2018. After that there “could be a Request for Proposals (RFP) to see if there’s interest from mining companies.”

Garth DeMont, a geologist with the Geoscience Branch of DNR (which was moved to the Department of Energy and Mines in July 2018), was quoted as saying, “All we need is the discovery of one significant gold vein and the Cobequids will light up.”

Mixed Acadian forests in the Cobequid Hills of northern Nova Scotia light up every autumn as the foliage on hardwood trees take on brilliant red, orange and yellow hues. Photo by Joan Baxter

DeMont said it would take a decade of exploration in the area before any mining would happen. If it did, there might be several mines operating.

He conceded that there was a “concern” about mining in a watershed, but then added, “… there’s an opportunity to have a milling component outside, in a different water draining water shed [sic].”

DeMont also claimed that the geologists had “been keeping residents informed, as well as the municipality” and working with the Tatamagouche Water Utility.

The French River watershed, in which government geologists want to promote gold exploration and mining, is the water supply for the village of Tatamagouche. Photo by Joan Baxter

It is safe to assume that everything in the article accurately reflects what he told the reporter, because – as DeMont requested – Tetanish sent him the article before it was published.

I obtained documents related to DNR’s Cobequid Hills project – or as DNR refers to it, “Warwick Mountain Gold” – through a freedom of information / protection of privacy (FOIPOP) request. The documents show that DeMont forwarded Tetanish’s unpublished article to his DNR colleagues. At least one made “corrections,” which were redacted in the FOIPOP documents. DeMont then sent the article back to Tetanish with changes highlighted in yellow and additional “educational text” offered in green, presumably to clarify any “inaccuracies.”[2]

Water worries

Despite the chance to comment on the article, the DNR team didn’t pick up on a few inconsistencies of their own.

The geologists had not “been keeping residents informed” as they had claimed in The Tatamagouche Light article. The November article was the first that most people in northern Nova Scotia had heard of the gold exploration. Nor had the geologists met with the Colchester or the Cumberland County municipal councils.

Rather, they had been meeting for two years with the French River Source Water Protection Advisory Committee Tatamagouche (sometimes called the Tatamagouche Watershed Protection Committee). The Committee had been formed in 2016 to develop a protection plan for what was a new treatment plant for the Tatamagouche Water Utility.[3]

The DNR geologists’ decision to meet regularly with the committee seems to have been prompted by fears that they might encounter resistance from those concerned about the watershed. DNR email correspondence shows that in 2015, DeMont informed his colleagues that Tatamagouche had had a source water protection plan since 2007.

That plan details all risks in the watershed, including recreational use of the area by All Terrain Vehicles, as well as prevalent industries such as forestry and agriculture.[4] On the risks of “pits, quarry and mining land activity,” the plan states, “Fortunately there are not many activities of this nature in the watershed. Pits quarries [sic] and mining activities by their very nature are an intrusive activity which can be prone to run off and causing issues of siltation and stream disturbance. Taken to the extreme, a mining operation can expose an area to tailings ponds, heavy metals and various other chemicals used in association with the mining operations.”

The watershed protection plan also notes that there are “some occurrences of uranium in the watershed but the provincial moratorium on exploration and mining has ended the business in Nova Scotia.”

In a November 16, 2015 email, DeMont alerts four DNR colleagues about this section of the 2007 plan, noting, “if you read the tone of the section on mining and quarries it will provide some perspective on the plan writers [sic] opinions on mining related activities in the watershed.” This led him to conclude: “Some education work is going to be required with the water shed [sic] management team and the sooner we start the better.”

In May 2016, DNR began to attend the bi-annual meetings of the Tatamagouche Watershed Protection Committee. Present at that meeting were DeMont and another DNR geologist, Trevor MacHattie, who presented information on the “Cobequid Highlands Geological Mapping Project.” According to the minutes of the meeting, also in attendance were three representatives of Nova Scotia Environment – David Blair, Carrie Miller and John Drage (in fact, the latter is with DNR).[5]

At the same meeting, Colchester Deputy Mayor Bill Masters, who sits on the committee, asked that they seek legal advice from the municipal council’s solicitor on the committee’s ability to control or prevent any mineral exploration within the watershed. Minutes from subsequent meetings do not mention this request.

DNR geologists continued to participate in the committee’s meetings but were not always consistent in what they told the committee.

In October 2016, the committee was told “actual mining is at least 5 years away.” A year later, that became 10 years.

DNR was also quite demanding in what it seemed to expect of the committee. In July 2017, Garth DeMont informed the committee that it would need to develop terms and conditions to be included within the Request for Proposals which will guide mining and exploration within the watershed.

At the next meeting in October 2017, DNR’s Geoffrey Baldwin told the committee that most [mining and exploration] companies were willing to work closely with local interests.[6] This is an audacious claim, given the steady stream of reports about the negative effects of gold mining on local communities around the world, and the frequency with which companies sue governments that try to protect their citizens and environments.

Various representatives from the Department of Environment were present at the meetings, including Michael Allen, the department’s “watershed planner,” at the one in October 2017. There is no evidence from the minutes that any of them informed the committee that the municipality had the right to apply to designate the Tatamagouche watershed a protected water area, which could determine what activities would and would not be permitted within it. As of 2013, there were 28 designated protected water areas in Nova Scotia, and in seven of these, “mine/pit/quarry/peat operations” were prohibited.[7]

Citizens rally

Following the publication of Tetanish’s November 2017 article, DNR geologists held an “open house” on a back road on Warwick Mountain, about 20km from Tatamagouche. They put up posters showing the mineral potential for the area and took questions from the few dozen people who attended.

In November 2017, DNR geologists hosted an open house in a remote location on Warwick Mountain to provide information on their plans to promote the area for gold exploration. Photo courtesy of Gregor Wilson

Two weeks later, a group of citizens attended – as observers only – the December meeting of the Tatamagouche Watershed Committee. There, DeMont suggested that the committee look to industry literature he had sent them to develop a list of “best practices” for mineral exploration in their watershed.

Following that meeting, a group of citizens wrote to DNR to ask that it delay its Request for Proposals for exploration for a year, giving residents time to understand what it would mean to have exploration and mining in the area.[8]

Two citizen members of the Watershed Protection Committee then organized an information session to gauge community feeling on whether the committee should be drafting “best practises” for mineral exploration in the watershed. The majority view at that meeting was that there were no “best practises” for mineral exploration or mining in a water supply.

This led to the formation of a citizens’ group called Sustainable Northern Nova Scotia (SuNNS), which launched a letter-writing campaign and undertook extensive research on gold mining. SuNNS organized a public Q&A in Tatamagouche on the basics of gold mining. Appearing on Skype, Ramsey Hart, former Canada program director for MiningWatch Canada, fielded questions. Asked whether there was any precedent for mining in a watershed, he replied that urban areas such as Vancouver and New York have gone to great lengths to reforest their watersheds and restrict even residential developments in drinking water watersheds. The idea of having a gold mine in one, Hart said, is “a non-starter.”

SuNNS members also gave presentations to the municipal councils in Colchester and Cumberland Counties. They spoke about the risks of gold mining in the Cobequid Highlands with its six watersheds, a part of the province that they argued had many other more sustainable business opportunities and activities than gold mining. They expressed their concerns about the risks to the Tatamagouche water supply, and asked the Colchester council to request that DNR delay issuing a request for proposals inviting mining companies to the area. The council agreed to do so.

Selling Nova Scotia

But it turns out that DNR had already been soliciting foreign companies and countries to come to the area – and was about to do so again at the 2018 PDAC convention.

Prospectors and government geologists shared a booth at the 2018 PDAC convention in Toronto, promoting Nova Scotia as a mining destination. Photo courtesy of Gregor Wilson

In a December 22, 2017 email response to concerned citizens, executive director of the geoscience and mines branch of DNR, Donald James, wrote that in March 2016 at the PDAC convention in Toronto, then-Minister of Natural Resources Lloyd Hines had promoted the Cobequids project area, its potential and the “Request for Proposal (RFP) concept to an audience of mining industry leaders, investors and indigenous leaders.”

In 2017, both Lloyd Hines and DNR Deputy Minister Julie Towers attended the PDAC convention, as did geoscientists Trevor MacHattie and Geoff Baldwin. In a report on the event, Garth DeMont wrote that, “DNR staff were joined in the Nova Scotia booth by Troy Sawler of Nova Scotia Business Inc. and Melissa Nevin of the KMKNO Mi’kmaq Rights Initiative.”[9]

Immediately after the 2017 PDAC convention, DNR sent out emails inviting several companies – IAMGOLD, Kenorland Minerals, Auryn Resources, Orix Geosciences Inc, Rio Tinto, Altius Minerals, Klondex Mines – to come to Nova Scotia to see the site and “have a firsthand look at the geology.”[10] The same year, DNR geologists travelled to Nevada to visit Klondex gold mines there.[11]

“Au!!!”

In January 2018, in response to a list of specific questions about the project, DNR spokesperson Bruce Nunn emailed me a general statement, which included this passage:

“Mineral exploration projects usually number in the thousands before one might reveal itself as having potential for development. Early stage mineral exploration has little or no effect on activities such as tourism, agriculture, forestry, hunting, angling, hiking, or other recreation. Typically, it involves small scale activities such as drilling holes, digging trenches, or geochemistry sampling. Mineral exploration activities can take up to 15 years to complete.”

Although Nunn downplays the chances of gold exploration ever leading to mining, among themselves, DNR geologists seemed far more convinced it will. Internal emails speak of “very high mineral potential.”[12] DNR’s economic geologist says he is “more confident than ever that we have a very good chance of it being a significant discovery,” and another geologist reports on findings that he says, “are bound to run to Au [gold]!!!”[13]

As for exploration, Nunn said in an email that, in general, these activities are “low disturbance,” and that “drilling for a mineral deposit is much like drilling a water well.”

According to Ugo Lapointe of MiningWatch, however, drilling can be very invasive, involving heavy equipment on bush trails and roads. Making holes in the rocks increases the mobility of contaminants in them, such as arsenic and uranium, which he says can then affect water sources.

The Nova Scotia Department of Environment, in a document called “Mineral Exploration and Development in Municipal Water Supply Areas,” offloads responsibility to municipalities to “manage and minimize impacts from activities that can potentially impair water quality in the source area,” without giving a municipality a clear right to prevent mineral exploration in its watershed.

Mineral exploration is permitted under the Mineral Resources Act. According to Donald James, Executive Director of DNR’s Geoscience and Mines Branch, “exploration companies may be required to comply with management strategies contained within municipal source water protection plans.”[14]

The NS Environment document also suggests that in Nova Scotia, mineral exploration companies should regulate themselves: “As a matter of good business practice, persons involved in mineral exploration are expected to take every precaution to protect the environment and respect local communities.”

It offers this description of what can happen under “advanced exploration activities.”[15]

“Activities: Detailed/advanced exploration may include activities such as drilling, test pitting, trenching/excavation, underground excavation, bulk sampling, stripping, road construction and watersource alteration. These activities are more invasive and disruptive and may require additional approvals.

Excavation Registration (DNR): An Excavation Registration is required for the following activities associated with excavation: trenching, blasting or stripping (by hand) to depths of over a metre, any exploration by mechanical means, and sampling of up to 100 tonnes of mineral-bearing material as well as de-watering and underground exploration. An Excavation Registration required by Section 101 of the Mineral Resources Act must be submitted to the Registrar of Mineral and Petroleum Titles at least 7 days before the commencement of the activities to be conducted under the Excavation Registration.

Letter of Authorization (DNR): Bulk samples (greater than 100 tonnes of mineral-bearing material) require a Letter of Authorization from the Registrar of Mineral and Petroleum Titles . . .

Water Approval (NSEL): A Water Approval must be obtained from Nova Scotia Environment and Labour for the use or alteration of any water course or wetland. This approval is required for activities such as, but not limited to, withdrawal, diversion, dam construction, in-filling, culvert or bridge installation, causeway construction or any other modification to a surface water course.”

All of this suggests that advanced mineral exploration can indeed be disruptive and potentially damaging to the environment. Yet such exploration can be conducted without jumping over many stringent regulatory hurdles. Once a company has a mineral lease from DNR (and there are nearly 1,000 of them in the province), the process of registering and getting government approval for an activity appears to be fairly routine, especially when that government is working so hard to promote mineral exploration.

Regulatory oversight, or regulatory capture?

This highlights both weaknesses and a gap in the environmental regulatory regime.

Environmental assessments and industrial approvals don’t come into the picture until an actual mine is proposed.

Mine proposals would be a natural outcome of the discovery of gold from exploration taking place at the explicit invitation of, and with encouragement and even financial incentives from, the government of Nova Scotia. Its Mineral Resources Development Fund offers grants to “assist prospectors, exploration companies, and researchers in the search for new discoveries, to advance projects closer to production, and to attract investment into the province.”

If the government is funding prospectors and exploration companies to find minerals, and investing heavily in promoting an exploration project and years of staff time to document it, it would make little sense for the government to turn around and prevent the development of a mine were gold discovered.

DNR emails show that when citizens expressed their concerns about these issues and the proposed mineral exploration in the Cobequid Hills to government officials and politicians, they were offered platitudes and form letters that did not address their specific questions.

They were told, for example, that under the new Mineral Resources Act, a company holding an exploration license would need to have a “community engagement plan” acceptable to the minister. “Should members of the community feel that the exploration company’s community engagement and opportunities for input haven’t been adequate, they will be invited to contact the Minister of Natural Resources,” who will then “review the effectiveness of the company’s engagement plan.”[16]

This is hardly reassuring, given the lack of clarity as to what constitutes a “community,” and the secrecy that surrounds the “Community Liaison Committees” that are mandated in Industrial Approvals for other large corporations working in Nova Scotia – Northern Pulp and Atlantic Gold, for example. Those committees are chosen by the companies, and their membership is not automatically available to the public.[17]

“Community engagement” does not mean legal rights, and the term can too easily be pinned to a project like a green fig leaf, especially when a “community” is divided because of hyped promises of jobs. Like the term “social license,” reportedly coined by a mining executive in 1997 and now frequently used in mining industry PR,[18] community engagement is a term entailing no legal requirements so it can mean just about anything.

DNR correspondence shows that the people of Nova Scotia have paid tens of thousands of dollars for the work in the Cobequid Hills. They footed the bills for DNR geologists’ trips to see gold deposits in Nevada they felt resembled those in Warwick Mountain and expenses associated with PDAC conventions in Toronto.

The internal correspondence, however, suggests that the civil servants in the geoscience and mines branch harbour some suspicion of – even disregard for – the citizens who contacted them about the project (and who pay their salaries). DNR emails refer to them as “the activists” and the “letter writing group,” to whom the geologists should not reply directly.

The geologists seem focused on promoting mineral exploration and mining, and uninterested in citizen concerns about the environmental hazards of gold mining in and around their communities, or worse, in their watersheds or on family land.

This clear stream is a tributary of the French River, which supplies Tatamagouche with its drinking water. Atlantic salmon have been seen in this stream. Photo by Joan Baxter

Concern for the consequences on the Cobequids

One of the SuNNS activists who has written to DNR and met with the Minister of Natural Resources, and later the Energy and Mines minister and government geologists, is Gregor Wilson. His dream is to see Wentworth Valley, and the Cobequid Hills that flank it, developed into a four-seasons eco-tourism destination. He points out that the ski hill, where he is a director, already draws as many as 80,000 visitors every year, and the October fall colours festival another few thousand. With the right protection, design and marketing, he believes the number of outdoor enthusiasts to the area could double and create many year-round businesses and jobs.

Wentworth Valley in the Cobequid Hills of northern Nova Scotia has immense potential as a four-season ecotourism destination, with its ski facilities, waterfalls, rivers and hiking trails. Photo by Joan Baxter

“Gold mining jobs are typically short-term,” Wilson tells me. “How many long-term sustainable jobs will one toxic spill kill in the Tatamagouche water source area? One spill in the French River could kill many agricultural, tourism and fishing jobs.” He says that in recent years, the area has experienced a small economic boom, with an award-winning organic brewery, several new organic farms, many new tourist attractions, activities, festivals, and infrastructure.

“Gold mines should not be permitted in headwaters of rivers, and certainly not in a community’s water source,” says Wilson. “It defies all logic and common sense.”

Others in the area are less vocal, but no less worried about the possibility of gold mining in the Cobequid Hills. One of those is Jim Bezanson, whose family runs Swan’s Maple Products in New Annan, just a few kilometres from Warwick Mountain and inside the closure area slated for exploration.

He avoids publicity (and declined to be photographed for this article), focusing his energy on his maple syrup operation, into which he has sunk more than $120,000 in recent years.

Jim Bezanson’s family’s sugarbush near Warwick Mountain, which, if government geologists have their way, will become a hotspot for gold exploration and mining. Photo by Joan Baxter

During a walk through his sugar bush, Bezanson says he began tapping with his father-in-law 41 years ago. Today, he has about 48 km of pipe connecting 6,500 trees he has tapped on more than 60 acres. Some are on land adjoining his that he leases, and some are on land that has been in his wife’s family since the 1800s. The trees are mostly 80 years old or younger, so they still have another 100 or 120 years of production left.

Although Bezanson has had no contact with DNR, he’s heard about the plans to open up the area for mineral exploration and gold mining. He’s not happy about those plans, but is resigned to the fact that, as he puts it, landowners have “no rights” when it comes to mining on their land. He says he wouldn’t fight an expropriation because he figures it would be a lost cause.

Bezanson is right; according to Ugo Lapointe of MiningWatch Canada, because of archaic laws and mindsets that date back to medieval Europe, Canada’s mining legislation and policies give mineral exploration and extraction priority over other possible land uses, even when “the value and merit of these alternative uses” are proven.[19]

“Prospecting and claim staking – the early phases of mineral development, often occur irrespective of who occupies, uses or owns the land on the surface,” writes LaPointe. This “free mining system appears fundamentally at odds with principles and values that call for greater environmental protection and more inclusive, equitable and participatory approaches to the development of land and resources.”

So even if Jim Bezanson and others in the area would like to see the Cobequid Mountains spared gold exploration and mining, existing laws do not protect them. For Bezanson, it isn’t a question of the monetary value of the land.

“It’s that it’s been in the family so long,” he says. “It’s where the kids and the grandkids come when the sap is flowing and we’re boiling.” And, he adds, it’s land his father-in-law cared for his entire life. He’s hoping one of his daughters will take over the business and the sugar bush once he can no longer manage it.

For now, he says he is just hoping “that the project doesn’t get anywhere, and that the whole plan goes away.”

“Fastest would be best,” he tells me.

Water not gold

Although government geologists had pledged to release the request for proposals in the summer of 2018, and to give the public two weeks to review and comment on it, that has yet to happen.

Although government geologists had pledged to release the request for proposals in the summer of 2018, and to give the public two weeks to review and comment on it, that has yet to happen.

However, in the meantime, SuNNS and the Municipal Council have been busy.

SuNNS members started a door-to-door exercise to get the views of people in the area and gauge public sentiment and knowledge about gold exploration and mining in the Tatamagouche watershed. According to SuNNS spokesperson, John Perkins, 99% of those questioned opposed the idea of gold exploration. Throughout the summer months, SuNNS “Water Not Gold” signs popped up on lawns and roadsides in and around Tatamagouche.

SuNNS also engaged the services of mining expert and aqueous geochemist Ann Maest, a specialist on the environmental effects of hard-rock mining, to look at the Warwick Mountain project reports available on DNR’s website. Maest has evaluated more than 150 environmental impact statements for large-scale mines on four continents, and published her research in peer-reviewed journals.

Maest’s findings were not reassuring. Drawing on DNR’s own research, she noted that mining in the province has “left a legacy of adverse effects to water quality, human health, terrestrial wildlife, and fisheries,” and historic mine tailings have released toxins such as arsenic and mercury into water bodies.

She also highlighted the disparity between the extensive amount of sampling DNR geologists did to detect minerals in the Cobequid Highlands, and the minimal amount of testing they did for water quality and evaluating potential environmental effects of mining in the area – a disparity she called “staggering.”

Maest noted that the DNR data show it did no groundwater evaluation in the area. They did test surface water, and found that the French River had low alkalinity. That meant the river would have “essentially no ability to neutralize any acid produced during exploration.”

Then in late August, the Tatamagouche Watershed Protection Committee met and passed two motions to take to the Colchester Municipal Council for approval. One was to launch the process to obtain protected status for the watershed with the Department of Environment, and to explicitly name mining as a prohibited activity in the watershed. The second was to make an official request that the Department of Energy and Mines delay issuing a request for proposals for exploration in the area until that process to protect the French River watershed was completed.

The municipal council approved both motions. Members of the Watershed Protection Committee acknowledged that the Minister of Energy and Mines had the legal right to override the protected status and an interdiction on mining in the watershed, but maintained that it was their duty to try to do something.

Shortly after that, in early September 2018, the Nature Conservancy of Canada (NCC) protected 904 acres (366 ha) of mature maple forest near the headwaters of the French River, and right in the heart of the area slated for gold exploration. The property was donated to NCC by descendants of the late Dr. George Cook, a surgeon and part-time maple syrup farmer. The new nature reserve is considered “ecologically significant,” with its diverse species of trees, the habitat it provides for birds (including two species listed under Canada’s Species At Risk Act), bear, bobcat and Nova Scotia’s endangered mainland moose.

None of this precludes gold exploration in the area; mining legislation in Nova Scotia gives absolute priority to above-ground resources over those that lie underground, and grants the Minister of Energy and Mines the power to allow mineral exploration and mining just about anywhere.

But for now, concerned citizens in the area say they are hoping that the government will eventually decide to protect water, and forego any gold that might be in the Cobequid Hills.

Next and last in the series: Part 4. How the mining lobby is working to undermine environmental protection in Nova Scotia

Footnotes

[1] The “preliminary surficial geological map of the closure area is available at: https://novascotia.ca/natr/meb/data/mg/ofm/pdf/ofm_2018-002_d501_dp.pdf [accessed May 28, 2018]

[2] Asked whether it was standard procedure for The Light to allow interviewees and sources to comment on articles in which they are quoted, Tetanish emailed this statement, “Advocate Media Inc.’s policy is we don’t allow subjects to dictate how a story is written. However, if a story includes technical information, we can send it to make sure the technical information is correct. It is made clear that is the only input we are seeking. There are times when sources respond with additional or educational information, but if it does not add to the story, that information isn’t included.”

[3] Municipality of Colchester. Terms of Reference: French River Source Water Protection Advisory Committee. July 5, 2016. Primary membership was to consist of: The Mayor or Deputy Mayor of the County of Colchester, the Area Councillor representing Tatamagouche in the Municipal Council (who would also chair the Committee), two citizen members representing the community, a representative of the North Shore River Restoration Group, representative from the Village Commission, Director of Public Works and Director of Community Development of County. Representatives from Nova Scotia Environment as Ex-Officio members.

[4] The 2007 French River Water Management Plan from the Municipality of Colchester is available at: https://www.colchester.ca/french-river-watershed [accessed May 28, 2018]

[5] French River Source Water Protection Committee. Minutes of meeting, May 2, 2016

[6] French River Source Water Protection Committee, Minutes of meeting held October 31, 2017, Tatamagouche

[7] Designated protected water areas in Nova Scotia. 2009. The seven watersheds in which mine/pit/quarry/ peat operations are prohibited are: Bennery Lake (HRM), Lake George (Yarmouth), McGee (Kentville), Forbes Lake (New Glasgow), North Tyndal Zones 1,2 and 3 (Amherst) https://novascotia.ca/nse/water/docs/ProtectedWaterAreasRegulations.pdf [accessed April 28, 2018]

[8] Disclosure: I attended this Watershed Protection Committee meeting and was a signatory on a citizens’ letter to Donald James, executive director of the geoscience and mines branch in DNR on December 8, 2017, requesting the RFP be delayed at least one year. I also attended the information session called by two citizen members of the Watershed Committee in January 2018. Internal DNR email correspondence and emails between Councillor Mike Gregory and Garth DeMont suggesting I “volunteered” to take minutes and that this was a meeting of “citizens opposed to mining” are erroneous. The meeting was an information session called by citizen members of the French River Source Water Protection Committee to gauge public opinion on whether the committee should put together “best management practices” for DNR’s RFP, and the organizers requested that I take minutes.

[9] Garth DeMont. Promoting Nova Scotia at PDAC 2017. The Geological Record 4(2): Spring 2017, pp 1 – 2. Available at: https://novascotia.ca/natr/meb/pdf/tgr.asp [accessed April 4, 2018]

[10] Emails, June 2017, from DNR Economic Geologist, to mining companies.

[11] Email, September 28, 2017, from DNR Economic Geologist to DNR Director of Geological Services

[12] Email, December 7, 2016, from Director of Geological Services, DNR

[13] Email, July 12, 2017, from DNR geologist

[14] Email, December 22, 2017, from Executive Director of DNR Geoscience and Mines Branch

[15] Passages from this document were sourced from a December 18, 2017 email from Garth DeMont to colleagues.

[16] Donald James. Email of December 22, 2017.

[17] The Department of Environment directed me to file a Freedom of Information request for details on the membership of the Community Liaison Committee for Atlantic Gold’s mine in Moose River.

[18] Business Council of British Columbia. Rethinking Social Licence to Operate – A Concept in Search of Definition and Boundaries. Environment and Energy Bulletin. Vol 7 (2): May 2015. http://www.bcbc.com/content/1708/EEBv7n2.pdf [accessed May 8, 2018]

[19] Ugo LaPointe. The legacy of the free mining system in Quebec and Canada. In: David Leadbeater (ed). Resources, Empire & Labour: Crises, Lessons & Alternatives. Haifax & Winnipeg: Fernwood Press. pp 147 – 158

Pingback/Trackback

September 17, 2018 @ 9:36 am